2017 Report to Congress

Young Adults and Transitioning Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder

This Report concerning young adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and the challenges related to the transition from existing pediatric and school-based services to those services available during adulthood is mandated by the Autism CARES Act of 2014 (P.L. 113–157, see Appendix 1 for the complete text of the relevant section of the legislation).

The purposes of this Report are to summarize existing federal investments focused on the transition period from childhood to adulthood for individuals with ASD, and to identify gaps in federal research, programs, and services that support youth with ASD during this critical time period.*

Part 1 of the Report provides background information on ASD and the need for support and services during the transition to adulthood. Part 2 presents an overview of federal programs that provide research, services, and supports applicable to youth and young adults with ASD. Part 3 summarizes information obtained from key stakeholders on this topic. Part 4 of the Report offers a synthesis of findings and recommendations for further consideration of systematic improvements in research, services, and supports focused on ASD and transition.

In this Report, 'services and supports' is used to convey the range of needs that youth and young adults with ASD may have, including health and behavioral health care, community-based supports and services, as well as support for tasks that all youth entering adulthood must navigate, such as obtaining employment, pursuing postsecondary education and training, managing independent living, and developing relationships and social networks that are meaningful to the individual.

The definition regarding what constitutes "transition age" varies. However, as a period of life that marks the transition from adolescence to adulthood, it is typically viewed as beginning in mid to late adolescence (e.g., ages 14 to 16) and ending in young adulthood (e.g., ages 24 to 26),1 roughly representing a period of time that typically encompasses not only most of high school, but also postsecondary education and training, and the establishment of employment and independent living.

Source references are included as endnotes following the Report and indicated in the text with Roman numerals; additional information that may be of interest to readers is included as footnotes at the bottom of the page and indicated in the text with symbols.

* These gaps were identified pursuant to statutory directions from Congress and as such do not constitute recommendations from the Administration for federal legislation.

Introduction to Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition. The American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (5th edition)2 identifies the diagnostic criteria for ASD as including:

- Persistent impairments in social interaction, including difficulties in social skills and nonverbal communications, as well as difficulty in developing, maintaining, and understanding implicit social norms regarding relationships with others; and

- Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, such as repetitive motor movements, inflexibility with regard to routines, restricted interests, and unusual reactions to sensory input.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), maintains an active epidemiological surveillance system that provides estimates of the prevalence and characteristics of ASD† among children aged eight years whose parents or guardians reside in 11 surveillance network sites in the United States. According to this Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, an estimated 1 in 68 eight-year-olds in the United States met the criteria for ASD in the most recently published report.3 The ADDM Network bases its estimate on standardized evaluation of educational and health care records that were submitted by qualified service professionals in network sites.

Although often diagnosed in childhood (most commonly after age four; widely accepted diagnostic tools do not exist for children younger than 18 months‡), ASD is a condition that typically continues throughout life and may be diagnosed in later childhood or even in adulthood. Because ASD is very heterogeneous in nature, its associated challenges and support needs can range widely from minor to very extensive.4 Regardless of the impact of associated challenges, youth with ASD should be able to access opportunities available to all youth entering adulthood in the United States, including pursuing life goals, participating in community life, and living independently (including living independently with assistance). Like any young adult, individual life goals may include opportunities to pursue postsecondary education and training, and to attain competitive and integrated employment.

Scope of Need

This section provides a description of the U.S. population with ASD and its needs, and serves as a foundation for understanding existing resources and potential gaps in those resources for those in the transition period.

Population Characteristics

National surveys that provide population-level data such as the National Survey of Children's Health (NSCH), the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN), and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)§ contain information on children through age 17 years, including the percentage of these with ASD. Data available from both the NSCH (200755 and 2011–20126) and the NHIS7 indicate that in addition to gender differences, socioeconomic and racial/ethnic variation exist in the reported prevalence of ASD in the U.S. child population. In particular, based on 2014 data from the NHIS,7 higher prevalence of ASD is found among the following groups:

- Males (75.0 percent of persons reported as having been diagnosed with ASD);

- Non-Hispanic white children (59.9 percent of persons with ASD);

- Children living:

- With families in large metropolitan areas (54.7 percent of persons with ASD);

- With two parents (68.0 percent of persons with ASD); and

- With at least one parent who had more than high school education (67.6 percent of persons with ASD).

These data, however, cover only the pediatric population (ages 0 through 17 years); thus, information that tracks prevalence of ASD into adulthood is not available from existing population-based national datasets.

The variation in reported prevalence across different racial/ethnic populations is likely not a true variation but instead may be due to uneven access to health care resources and services that enable early identification and diagnosis of ASD across different racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups; this hypothesis is consistent with the fact that the socioeconomic and racial/ethnic gap in ASD diagnosis has decreased over the past decade as awareness of ASD has increased across a broader range of medical and other service providers.8 There is also evidence that girls with less extensive support needs are underdiagnosed with ASD as compared to boys with similar support needs.9, 10

In addition to population-based surveys of children's health, the National Longitudinal Transition Study 2012 (NLTS 2012) recently released data comparing middle school and high school youth with ASD to youth with other disabilities as defined under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).8 Data for the NLTS 2012 were collected in 2012–2013 from approximately 12,000 in-school youth and their parents, of which about 10,000 are students receiving special education and related services¶ under the IDEA. These students represent each of the 13 federal disability categories, including autism. Demographic findings from the NLTS 2012 report are consistent with other national survey data presented above. In particular, statistical analyses indicated that youth with ASD, when compared to students receiving special education and related services under IDEA overall, are significantly:

- More likely to be male (84 percent versus 67 percent);

- Less likely to be from socioeconomically disadvantaged families (37 percent versus 58 percent);

- Less likely to be Black not Hispanic (12 percent to 19 percent) or Hispanic (16 percent versus 24 percent); and

- More likely to have at least one parent with a four-year college degree (43 percent versus 26 percent) and parents who are married (72 percent versus 63 percent).

It is important to note that under the IDEA, autism is defined in part as “a developmental disability significantly affecting verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction, generally evident before age three that adversely affects a child's educational performance” (34 CFR §300.8(c)(1)(i)). The focus on adverse impact on educational performance is appropriate given the purpose of the IDEA. Yet, due to the heterogeneous nature of ASD,4 not all youth and young adults with autism have concurrent intellectual disability** or behavioral issues that interfere with their performance or conduct in the classroom; instead, their condition may be primarily evident in social interactions with peers at recess or outside of school. Thus, although the NLTS 2012 generalizes to students in special education, it is not representative of the entire population of youth with ASD, but only to those who experience adverse impact on educational performance because of ASD and qualify for and receive special education and related services under the IDEA.11

However, peer challenges in childhood and adolescence, including experiences of bullying, have been linked to social and emotional challenges (such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation) both concurrently and in adulthood.12 One study found prevalence estimates regarding bullying†† among adolescents with ASD to be 46.3 percent for victimization, 14.8 percent for perpetration, and 8.9 percent for behavior that combines victimization and perpetration.13 This compares to overall prevalence of being bullied on school property for students in grades 9 to 12 of 20.2 percent. Because social interaction challenges are a defining characteristic of ASD, it is important to understand and address the potential needs of all youth and young adults with ASD.

In conclusion, there is no currently available single national dataset that provides information on the full population of transition-aged youth with ASD. Instead, existing national surveys that provide data on the health of the U.S. child population, such as the NSCH and NHIS, report on autism only through age 17 years; the NLTS‡‡ and NLTS 2012 include data for persons across the full transition age range but include only youth with ASD who qualify for special education and related services under the IDEA.

Trends in Health and Well-being

The 2017 National Autism Indicators Report14 states that approximately 50,000 youth with ASD turn 18 each year, and that there are currently about 450,000 youth with ASD aged 16–24 years old in the United States. This estimate is derived from two separate sources:11 prevalence estimates from CDC's ADDM Network, combined with U.S. Census estimates regarding the number of 18-year olds in the United States in a given year.

As with all youth, these 450,000 adolescents and young adults with ASD, and those who come after them, should have the opportunity to find meaningful roles in adult society through competitive integrated employment, independent life skills, good health and well-being, satisfying relationships, continued education and training, and career development and exploration according to their individualized life goals.

The National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2),§§ commissioned by the U.S. Department of Education and conducted between 2000 and 2009, draws from a population of youth with disabilities who, at the beginning of the study, were enrolled in special education with an IEP in school; in 2009, they had exited secondary school and were 20–25 years old. Findings from both the NLTS2 and the NLTS 2012 (described in the preceding section) generalize nationally to special education students as a group, as well as to each of 13 disability categories including ASD that receive special education. Together, the NLTS 20128 and NLTS215 provide information regarding the health and wellbeing of youth and young adults with ASD who either qualify or qualified for special education and related services while in secondary school.

Trends in Secondary School

As described above, the NLTS 2012 compared middle school and high school youth with ASD to youth with other disabilities; all of these youth received special education and related services under the IDEA.8 This study found that youth with ASD who receive special education and related services under IDEA, compared to all students receiving special education and related services under IDEA are:

- More likely to have a co-occurring chronic health or mental health condition (43 percent versus 28 percent);

- Less likely to be able to manage independently and develop friendships:

- More likely to experience challenges communicating (50 percent versus 29 percent);

- Less likely to independently manage activities of daily living (17 percent versus 46 percent);

- Less likely to know how to make friends (76 percent versus 92 percent); and

- Less likely to report getting together with friends weekly (29 percent versus 52 percent).

- Less likely to take steps to prepare for college and employment:

- Less likely to be given at least some input into IEP and transition planning (41 percent to 59 percent);

- Less likely to have taken a college entrance or placement test (29 percent to 42 percent); and

- Less likely to have paid work experiences in the past year (23 percent to 40 percent).

In summary, compared to other youth receiving special education and related services, youth with ASD are more likely to have co-occurring health and mental health conditions, less likely to be able to manage independently and develop friendships, and less likely to take steps in secondary school that will prepare them for college and employment.

Trends in Adulthood

Data from the NLTS2, which examined young adults aged 20–25 with ASD who had been in special education in secondary school, indicate that:15, 16

- Less than 1 in 5 (19 percent) had ever lived independently (away from their parents without supervision) following high school (compared to more than 66 percent for those with serious mental illness or 34 percent with intellectual disabilities not concurrent with ASD);

- Nearly two-thirds (63.9 percent) received Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits;

- Only 58 percent had ever worked during their early 20s compared with those with other types of special health care and service needs, including emotional disturbances, speech and language impairments, and learning disabilities (all greater than 90 percent) as well as intellectual disabilities (74 percent); and

- Only 36 percent of youth with ASD had ever participated in postsecondary education or training of any kind between high school and their early 20s.

In addition, recent research has revealed disturbing trends in the early mortality of adults with ASD. Although further research is needed to confirm these findings, several studies have found that adults with ASD, compared to the general population:17, 18, 19, 20

- Die an average of 16 years earlier than people not on the spectrum;

- Are 40 times more likely to die prematurely of a neurological condition (such as epilepsy) if they also have a learning disability;

- Are nine times more likely to die from suicide;

- Are at heightened risk for co-occurring conditions such as depression and anxiety; and

- Are at higher risk for other non-communicable diseases including diabetes and heart disease.

Identifying what factors drive these differences, and improving services and supports to ameliorate or prevent co-occurring health and mental health conditions through the transition to adulthood and beyond, is thus a critical need for youth with ASD; this is an important component of what would be considered a tertiary public health prevention effort.¶¶ Such efforts may be shown to have significant returns on investment (ROI), and require monitoring and evaluation to support the evidence for such returns. Adults with ASD who receive supportive services have a high likelihood of subsequently gaining employment, thus improving the ROI for timely services.21

Transition Needs

The goals of transition planning and services—that is, preparing for the transition from adolescence to adulthood—include promoting career exploration and development, extending education or training opportunities, supporting independent life skills, and enhancing health and well-being.

Federal law requires schools to provide special educational and related services, including transition services, for students with ASD who meet the eligibility criteria under IDEA. However, the legal mandate for this provision ends following graduation from high school with a regular high school diploma, leaving many young adults with ASD who have either finished high school with a regular high school diploma, or aged out of IDEA requirements,*** without the continuing services and supports they may need. The 2015 National Autism Indicators Report: Transition into Young Adulthood16 examined 12 services that adolescents and young adults with ASD commonly use, including speech-language therapy, occupational therapy, social work, case management, transportation, and/or personal assistant services. During high school, nearly all (97 percent) received at least one of these 12 services. However, service usage dropped sharply following high school. In their early 20s, 37 percent were defined as “disconnected”—that is, they neither worked outside the home nor continued education after high school; 28 percent of these young adults that were neither employed nor attending postsecondary school or training were receiving no services or supports.

In 2016, the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC) collected public comments regarding the most pressing needs that stakeholders believe should be addressed in the 2016–2017 update of the IACC Strategic Plan. In the area of transition to adulthood, themes that emerged from public comment were:

- An acute need exists for a range of services and supports, including:

-

- Postsecondary education and vocational training;

- Employment opportunities;

- Treatment for concurrent conditions, and access to occupational, speech, and language therapies;

- Housing;

- Transportation supports;

- Community integration services and supports; and

- Coordinated, 'wraparound' services—that is, services in which a team of individuals relevant to a young person's health and well-being (e.g., family members, other supports, service providers, agency representatives) collaboratively develop an individualized plan of services and supports that they implement, evaluate, and revise as necessary over time.

- Relief is needed for the adverse challenges faced by families and individuals who face barriers to access, coordinate, and finance what are experienced as 'piecemeal' services on their own, or services that, in many cases, they may not even be aware of; and

- Transition supports and information should be provided beginning in early adolescence.

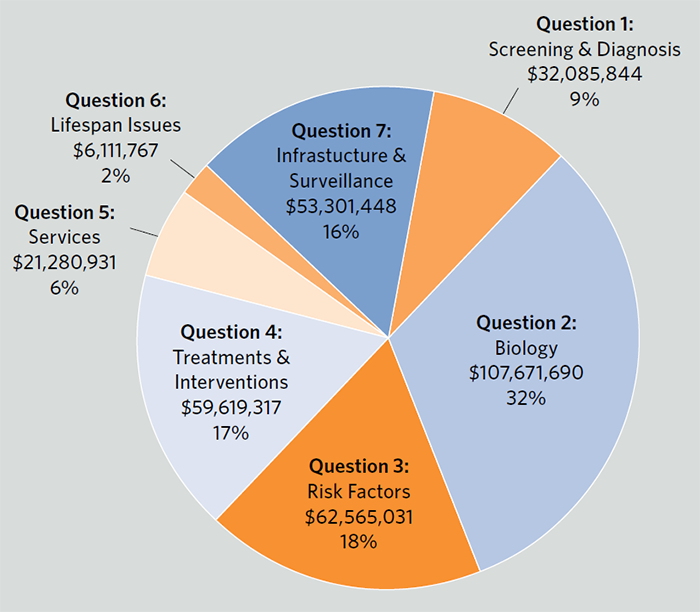

The IACC tracks U.S. federal and private research funding in its annual ASD Research Portfolio Analysis Report. Data reported for 201522 indicated that combined federal and private funding related to lifespan issues, which includes transition, received only 2 percent ($6.1 million) of overall federal and private ASD research funding (Source: Office of Autism Research Coordination, National Institutes of Health); this percentage does not change when including only federal funding sources.††† When considering only projects related to transition issues, the proportion is less than 2 percent of total funding. In terms of number of projects rather than percentage of funding, lifespan issues made up only 3 percent of ASD projects, with 37 projects across both federal and private sources; of these, 24 addressed transition to adulthood research.

††† Federal agencies included in the 2015 IACC ASD Research Portfolio Analysis: Administration for Community Living (ACL). Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Department of Defense, Department of Education, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Science Foundation (NSF). Private organizations included: Autism Science Foundation, Autism Research Institute, Autism Speaks, Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, Center for Autism & Related Disorders, New England Center for Children, Organization for Autism Research, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Simons Foundation.

Figure 1: ASD Research Funding by IACC Strategic Plan Question — Combined Federal and Private Funding

2015 Total Funding: $342,636,029

NOTE:Topic areas are defined by each question in the IACC Strategic Plan. Question 6, which focuses on issues across the lifespan, represents only 2 percent of the overall ASD research funding across both federal and private funding sources. SOURCE: Office of Autism Research Coordination, National Institute of Mental Health.

Challenges and Barriers to Service

ASD is a complex and heterogeneous condition, affecting different individuals in different ways and with differing experiences of barriers and challenges. Many of the barriers to services associated with ASD are common across children and youth with special health care, educational, and service needs;‡‡‡ other barriers are more specific (although not unique) to ASD itself.

Like many individuals with disabilities and/or special health care and service needs, transition-age youth and young adults with ASD may experience barriers23 around issues such as:

- The coordination of complex clinical care and service and support needs across multiple systems;

- Access to needed resources, which may be limited by availability of specialists and related services, as well as by adequacy of health insurance (with respect to health care services) and/or location of services;

- Access to services and supports that facilitate individual and family management of the financial, personal, and social challenges and barriers related to managing a complex, neurodevelopmental condition, and co-occurring health conditions;

- Achievement and management of independent living, including housing and transportation, as well as education and training appropriate to the individual's goals, career interests, and necessary employment supports, and other resources that any young person would need to enter adulthood and independently navigate its demands; and

- The development of meaningful relationships and broader social networks as the individual desires.

Challenges that are more specific but not necessarily exclusive to ASD include:

- Lack of availability of and consistency in ASD-specific training across a range of providers and provider types, which complicates identification, diagnosis, service provision, and access to needed supports and services; inconsistency in provider training and screening procedures is problematic for the quality of services that are available;

- The communication challenges faced by adults with ASD in accessing and interacting with health service providers about their physical and mental health; in addition, the lack of provider understanding of these barriers faced by their patients or clients with ASD may hinder delivery of quality healthcare services for this population; and

- A need to build greater community awareness and acceptance regarding the potential strengths and weaknesses that transition-age youth and young adults with ASD may bring to both workplace and community settings. This includes finding and maintaining competitive integrated employment; obtaining community-based housing; utilizing transportation services that enable independence and employment; and handling stigmatization, bullying, and victimization.24 These data suggest the need among employers, schools, care and service providers, and the public for greater awareness and acceptance of the neurodevelopmental differences associated with ASD.

‡‡‡ The HRSA Maternal and Child Health Bureau defines children and youth with special health care needs as those who have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral or emotional conditions and who also require health and support services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/maternal-child-health-topics/children-and-youth-special-health-needs.

Background for this Report

This Report is mandated by the Autism Collaboration, Accountability, Research, Education and Support Act (Autism CARES Act) of 2014 (P.L. 113–157).25 It was led by an Interagency Work Group comprised of a Steering Committee (led by the National Autism Coordinator in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health and the Office of Autism Research Coordination in the National Institute of Mental Health), and representatives from each of the federal agencies that support research and program efforts relevant to youth with ASD who are transitioning to adulthood.

Legislation

The Autism CARES Act

The Autism CARES Act was signed into law on August 8, 2014 (see Appendix 1 for the section of the Autism CARES Act that mandates this Report). An amendment to the Public Health Service Act, the Autism CARES Act reauthorized funding that began in fiscal year 2006 as the Combating Autism Act (CAA), and continued in fiscal year 2011 as the Combating Autism Reauthorization Act (CARA). The Autism CARES Act reauthorized activities related to ASD research, services, and support, including but not limited to:

- Epidemiological studies and research on ASD and other developmental disabilities;

- Autism-related educational services, early detection, and intervention;

- Support for regional centers of excellence in ASD for research and training;

- Use of research centers or networks for the provision of training in respite care and for research to determine practices for interventions to improve the health and well-being of individuals with ASD;

- The addition of language that includes adults as well as children as the focus of funded activities; and

- A report to Congress on federal activities related to youth and young adults with ASD and the challenges they face regarding the transition from school-based to adult service systems.

Legislative Requirements of the Report to Congress

The 2014 Autism CARES Act specifies the elements of this report in an amendment to Section 399DD of the Public Health Service Act (42 USC 280i-3). The exact wording is provided below and in Appendix 1:

- Demographic characteristics of youth transitioning from school-based to community-based supports;

- An overview of policies and programs relevant to young adults with autism spectrum disorder relating to post-secondary school transitional services, including an identification of existing Federal laws, regulations, policies, research, and programs;

- Proposals on establishing best practices guidelines to ensure:

- Interdisciplinary coordination between all relevant service providers receiving Federal funding;

- Coordination with transitioning youth and the family of such transitioning youth; and

- Inclusion of the individualized education program for the transitioning youth as prescribed in section 614 of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (20 U.S.C. 1414);

- Comprehensive approaches to transitioning from existing school-based services to those services available during adulthood, including:

- Services that increase access to, and improve integration and completion of, post-secondary education, peer support, vocational training (as defined in section 103 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (29 U.S.C. 723)), rehabilitation, self-advocacy skills, and competitive, integrated employment;

- Community-based behavioral supports and interventions;

- Community-based integrated residential services, housing, and transportation;

- Nutrition, health and wellness, recreational, and social activities;

- Personal safety services for individuals with autism spectrum disorder related to public safety agencies or the criminal justice system; and

- Evidence-based approaches for coordination of resources and services once individuals have aged out of post-secondary education;

- Proposals that seek to improve outcomes for adults with autism spectrum disorder making the transition from a school-based support system to adulthood by:

- Increasing the effectiveness of programs that provide transition services;

- Increasing the ability of the relevant service providers described in (C) above to provide supports and services to underserved populations and regions;

- Increasing the efficiency of service delivery to maximize resources and outcomes, including with respect to the integration of and collaboration among services for transitioning youth;

- Ensuring access to all services necessary to transitioning youth of all capabilities; and

- Encouraging transitioning youth to utilize all available transition services to maximize independence, equal opportunity, full participation, and self-sufficiency.

Coordination of Autism Activities

The Autism CARES Act makes provision for the coordination of autism activities across federal agencies. In particular, the 2014 Autism CARES Act:

- Reauthorizes the IACC to continue through 2019;

- Requires the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to designate an official (the National Autism Coordinator) to ensure implementation and accountability of Autism CARES activities, and to take the lead for writing this mandated Report to Congress on young adults and transitioning youth; and

- Requires the submission of two Reports to Congress—one that covers all federal autismrelated activities, and this current report, which focuses on the service needs of individuals with ASD who are transitioning into adulthood.

The Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC)

The IACC is a federal advisory committee comprised of public and private members that coordinates autism efforts and provides advice to the Secretary of Health and Human Services on ASD. The membership of the IACC includes officials from agencies supporting programs that serve individuals with autism, public stakeholders representing the viewpoints of individuals on the autism spectrum, family members, community advocates, community-based providers, and researchers. The IACC serves as a forum for public input on issues related to ASD, and the committee uses this input to inform its activities, including the annual update of the IACC Strategic Plan for ASD. In addition, the committee monitors federal and community activities related to ASD through its annual Portfolio Analysis Reports, and it compiles an annual IACC Summary of Advances in ASD Research to inform Congress and the public of major advances in ASD research.xxvi New provisions within the Autism CARES Act include a call for the IACC to increase focus on services and supports for people with ASD. The IACC is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health's (NIMH) Office of Autism Research Coordination (OARC).

National Autism Coordinator and Federal Interagency Work Group

As described in the 2014 legislation, the role of the National Autism Coordinator is to ensure implementation and accountability of Autism CARES activities. The Coordinator was appointed in April 2016, and convened, in October 2016, a federal interagency work group (IWG) to provide input into the mandated Report to Congress on young adults and transitioning youth with ASD; the IWG consists of representatives from multiple agencies across the federal government (Table 1). The National Autism Coordinator and IWG align and coordinate their efforts with OARC, which manages the IACC; the IACC includes members from several federal departments and agencies as well as public stakeholders. The IWG members have reviewed and commented on this Report. No appropriations were provided for required coordinating activities under the 2014 Autism CARES Act, but this Report has been completed by HHS using existing personnel and resources.

Government Accountability Office Report on Youth with Autism

In compiling this report, the IWG Steering Committee also drew information from the 2017 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, Youth with Autism: Roundtable Views of Services Needed During the Transition into Adulthood, GAO-17–109.4 GAO's report describes the highly heterogeneous nature of ASD, with varying levels of impairment (from none to severe) across five domains of functioning: social impediments; communication difficulties; intense focus/interests; sensitivities; and routine and repetition. This variation means that life goals, as well as specific life challenges that each of these goals may entail, are highly individualized. (Further detail on this 2017 GAO report is found in Part 4.)

In addition, in its 2012 review, Students with Disabilities: Better Federal Coordination Could Lessen Challenges in the Transition from High School, GAO-12–594,27 GAO found that students with disabilities face several longstanding challenges in accessing services that may assist them as they transition from high school into postsecondary education and the workforce—services such as tutoring, vocational training, and assistive technology. That report recommended that the U.S. Departments of Education (ED), Health and Human Services (HHS), Labor (DOL), and the Social Security Administration (SSA) develop an interagency transition strategy that addresses (1) operating toward common outcome goals for transitioning youth; (2) increasing awareness of available transition services; and (3) assessing the effectiveness of their coordination efforts. All four agencies agreed with the recommendation.

Summary of Background Information

The transition period from adolescence to adulthood for persons living with ASD involves increased challenges for those persons, their caregivers, and for government agencies and non-governmental organizations serving them. These complexities begin with the heterogeneity of the condition itself and any co-occurring health and mental health conditions, and become magnified by the complexities in transitioning from a largely educational system-based set of supports for those 21 years or younger, to a set of health and social service systems geared to adults. Many of these adult systems encompass general disability program services, but the eligibility requirements for them are in themselves challenging and perhaps not sufficiently coordinated for the individual client or even widely accessible to the ASD transitioning population.

Table 1: Participating Federal Agencies in the Interagency Work Group on Young Adults and Transitioning Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Steering Committee, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Office of the Secretary

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, National Autism Coordinator

National Institutes of Health

- Office of Autism Research Coordination

Federal Agencies Represented by Interagency Work Group Members

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Legislation

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response

- Office of Global Affairs

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration

Administration for Children and Families

- Children's Bureau

- Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Early Childhood Development

Administration for Community Living

- Administration on Disabilities

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- Office of Extramural Research, Education, and Priority Populations

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

- Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services

Food and Drug Administration

- Division of Psychiatry Products

Health Resources and Services Administration

- Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Division of Maternal and Child Health Workforce Development

Indian Health Service

- National Council of Chief Clinical Consultants

National Institutes of Health

- National Institute of Mental Health

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration

- Center for Mental Health Services

Office of Postsecondary Education

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services

- Office of Special Education Programs

- Rehabilitation Services Administration

Office of Civil Rights

Institute of Education Sciences

- National Center for Education Statistics

- National Center for Education Evaluation

- National Center for Special Education Research

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs

- Autism Research Program

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT

Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity

- Office of Enforcement, Compliance and Disability Rights Division

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

Civil Rights Division

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

Office of Disability Employment Policy

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

Federal Highway Administration

U.S. SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION

Office of Disability Policy

† In this Report, the terms autism, autism spectrum disorder, and ASD will be used interchangeably.

‡ Researchers continue to explore indicators of autism in the first 18 months of life with some promising results, although no widely accepted screening tool exists for children younger than 18 months. See Giserman Kiss I, Feldman MS, Sheldrick RC, Carter AS. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47:1269. doi:10.1007/s10803–017. Providers need to continue to be alert to signs of ASD throughout the first three years of life and to signs of undiagnosed ASD in all children, youth, and adults.

§ The NSCH and NS-CSHCN are led by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) at CDC, under the direction and sponsorship of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) at the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The NHIS is a data collection program of the NCHS, within CDC.

** 31.6 percent of children with ASD have a concurrent intellectual disability, defined as IQ equal to or less than 70; 43.9 percent are average or above in their intellectual ability.

†† Children and youth with disabilities have been found to be two to three times more likely to have experienced bullying than youth who do not have a disability. The CDC's 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey reported 20.2 percent overall prevalence of being bullied on school property for students in grades 9–12. Little is known regarding the relative prevalence of bullying among different subpopulations of youth with disabilities.

‡‡ The NLTS2 is discussed in more detail in the next section

§§ For information and reports based on the now-completed NLTS2 study sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education, visit its website at https://nlts2.sri.com/index.html

¶¶ Primary prevention involves interventions prior to the onset of a condition (such as risk factor reduction); secondary prevention involves interventions during early signs or pre-clinical states in order to prevent full expression of the condition; and tertiary prevention involves interventions after onset of the condition that prevent further disability or progression of disease.

*** As detailed in the 2017 GAO report on youth with autism, IDEA-eligible students can receive transition services under IDEA until they graduate from high school with a regular high school diploma or exceed the age range for which a given state makes a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) available to children with disabilities. Although federal law permits States to use IDEA funds to make FAPE available to students with disabilities who have not graduated high school with a regular high school diploma through age 21, whether States make FAPE available to students in this age range depends on state law or practice. Some States choose to terminate the obligation to make FAPE available when a student turns 21, and other States choose to continue to make FAPE available through a student's 22nd birthday.

†† Federal agencies included in the 2015 IACC ASD Research Portfolio Analysis: Administration for Community Living (ACL). Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Department of Defense, Department of Education, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Science Foundation (NSF). Private organizations included: Autism Science Foundation, Autism Research Institute, Autism Speaks, Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, Center for Autism & Related Disorders, New England Center for Children, Organization for Autism Research, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Simons Foundation.

‡‡‡ The HRSA Maternal and Child Health Bureau defines children and youth with special health care needs as those who have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral or emotional conditions and who also require health and support services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/maternal-child-health-topics/children-and-youth-special-health-needs.